BECOME ITALIAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

DIVE INTO A LIFESTYLE

From the rise of the Roman Empire to the enduring beauty of the Renaissance and the energy of contemporary design, Italy stands as a symbol of cultural richness in global history. Italy’s immense cultural heritage reflects influences from Etruscan, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, Germanic, and countless regional traditions—all woven into a uniquely Italian identity. Combined with its breathtaking landscapes, from the Alps to the rolling hills of Tuscany and the iconic cities like Rome, Florence, Venice, and Milan, Italy offers an unforgettable journey through its complex and timeless legacy.

After the unification in the 19th century and the turbulent events of the 20th, including fascism, world wars, and reconstruction, Italy entered a period of renewal marked by creativity, resilience, and innovation. Today, it remains a central force in art, fashion, cuisine, architecture, and global diplomacy—balancing its historical legacy with the demands and dynamism of the modern world. Italian influence on global culture has been both bold and subtle, leaving its mark on cinema, design, music, gastronomy, and literature—often as a symbol of beauty, elegance, and expressive depth.

We have created a selection of words that you won’t find in any textbook or course to help you not only sound like a true native speaker, but also introduce you to Italian words that carry a deeper cultural meaning.

Speak and think like a real Italian!

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Italian, we recommend that you download the Complete Italian Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't find in any textbook so you can amaze your Italian friends or business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

With a one-time purchase you will also get 10 hours of Podcasts to Practice your Italian listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Italian today!

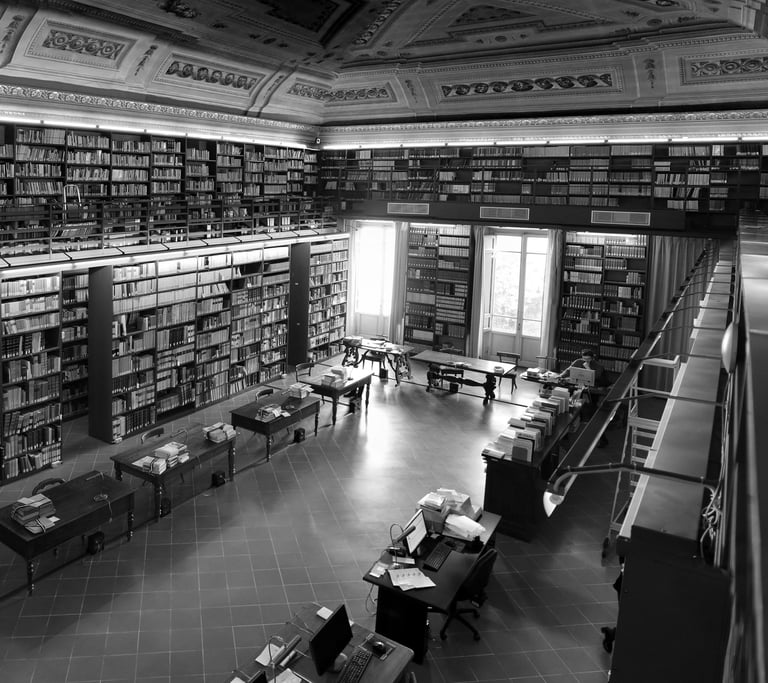

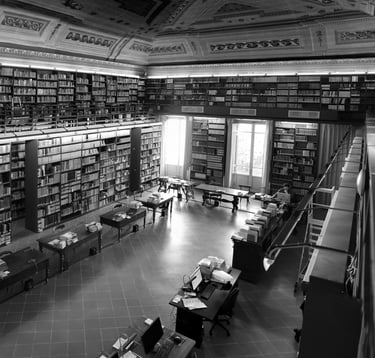

ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA

The Accademia della Crusca (Academy of the Bran) is one of the most important cultural institutions in Italy and among the oldest linguistic academies in the world. Founded in Florence in 1583, its main mission has been the preservation, study and promotion of the Italian language. The name derives from the metaphor of separating the crusca” (bran) from the farina (flour), symbolizing the effort to distinguish pure, correct language from impure or corrupted forms. The Accademia della Crusca quickly became a central reference point for writers, and scholars seeking to standardize Italian at a time when dialects were dominant across the peninsula.

One of the most significant contributions of the Accademia della Crusca was the publication of the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca (Dictionary of the Academicians of the Crusca) in 1612. This was the first dictionary of a modern European language and provided definitions, examples, and literary quotations that established models for correct usage. The dictionary gave prestige to the Tuscan dialect, particularly the Florentine variety used by authors such as Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, and it reinforced Florence’s central role in shaping the Italian language. Later editions of the Vocabolario influenced other European academies, including the Académie Française.

The role of the Accademia della Crusca has not been limited to historical dictionaries. Over centuries, it has expanded its activities to include philological research, linguistic consultancy, and educational initiatives. It publishes the journal Studi di lessicografia italiana (Studies of Italian Lexicography) and maintains collaborations with universities and cultural institutions in Italy and abroad. By responding to users on everyday doubts about Italian, the Accademia della Crusca continues to maintain its relevance and authority in the internet age.

The headquarters of the Accademia della Crusca are located in the Villa di Castello near Florence, a historic Medici villa that also houses a remarkable library and archive which contains over 250,000 volumes, including early printed editions, grammars, dictionaries, and manuscripts dating from the sixteenth century onward, making it one of the most important specialized collections for Italian linguistics worldwide. The archive preserves the original working materials of the Vocabolario, including cartigli (citation slips) used by scholars to document authentic literary usage.

ACETO BALSAMICO

Aceto balsamico (balsamic vinegar) is one of Italy’s most prized culinary treasures, known for its complex flavor, rich color, and deeply rooted traditions. Originating from the Emilia-Romagna region, particularly from the towns of Modena and Reggio Emilia, aceto balsamico tradizionale (traditional balsamic vinegar) is made through a centuries-old process that requires patience, craftsmanship, and a deep respect for heritage. Unlike commercial vinegars found on supermarket shelves, true aceto balsamico tradizionale is aged for a minimum of 12 years and can even exceed 25 years, earning the label extravecchio (extra old). This slow aging process takes place in botti (barrels) made of different types of wood such as cherry, oak, chestnut, and mulberry, each of which imparts a unique layer of flavor and aroma to the liquid.

The production begins with mosto cotto (cooked grape must), which is the freshly pressed juice of Trebbiano or Lambrusco grapes that has been slowly simmered until thick and caramelized. This is the only ingredient used in traditional balsamic vinegar, with no additives or preservatives. Over the years, the vinegar is transferred from one botte to another, gradually concentrating in flavor and reducing in volume through natural evaporation. The final product is a glossy, syrupy liquid with a perfect balance of sweetness and acidity, carrying complex notes of wood, fruit, and spice.

The art of making aceto balsamico tradizionale is protected by the Consorzio di Tutela (Consortium for Protection), which ensures strict adherence to traditional methods and grants the DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) label only to vinegars that meet their rigorous standards. Each bottle is sealed with a numbered label and a unique bottle shape designed by the Italian designer Giugiaro, serving as a guarantee of authenticity.

Aceto balsamico di Modena IGP (balsamic vinegar of Modena PGI) is a different, more widely available product that includes a blend of mosto cotto, wine vinegar, and sometimes caramel for coloring. While it is less expensive and aged for a shorter period, it still holds an important place in Italian cuisine and is ideal for everyday use.

Balsamic vinegar is used in a wide variety of dishes, from insalate (salads) and carne (meat) to formaggi (cheeses) and even gelato (ice cream). A few drops of high-quality traditional balsamic can elevate simple ingredients into a gourmet experience. Its intense yet balanced profile reflects the soul of Italian culinary philosophy: respect for the ingredient, time, and tradition.

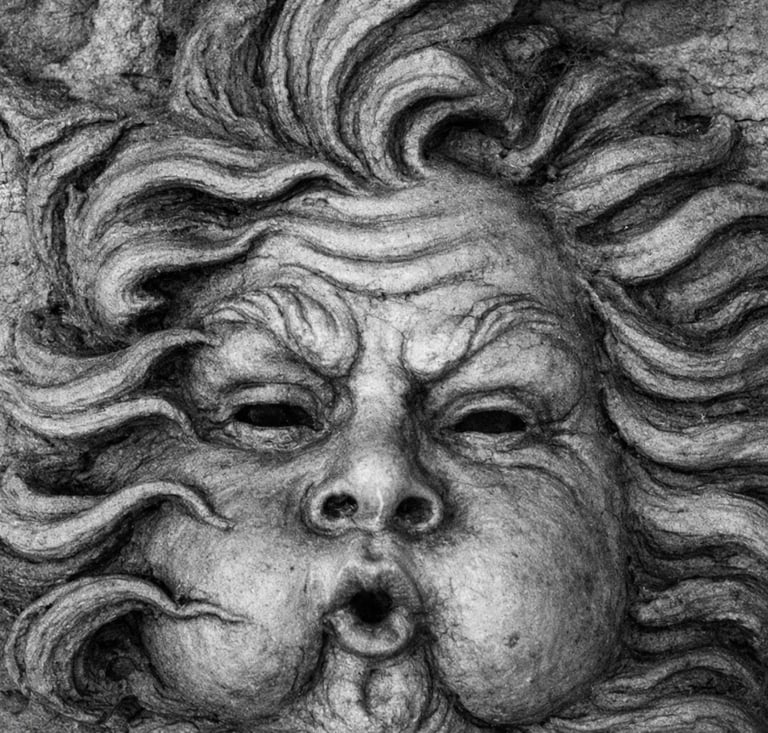

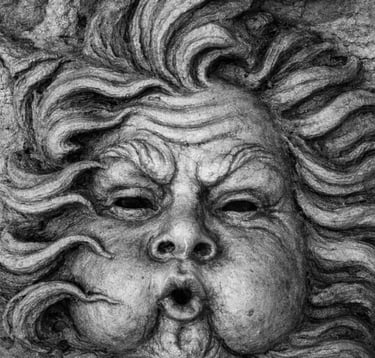

BAROCCO

Barocco (Baroque) is a defining artistic and cultural movement that emerged in Italy in the late 16th century and flourished throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries. It left an indelible mark on architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, and music, influencing all of Europe and extending beyond. The term itself, barocco, originally carried a slightly negative connotation, suggesting something irregular or overly ornate, but it has since come to represent one of the most innovative and expressive periods in Western art history. In the Italian context, the arte barocca (Baroque art) was not simply decorative—it was a powerful tool of communication, particularly during the Controriforma (Counter-Reformation), when the Catholic Church used dramatic imagery and grandeur to inspire faith and awe.

Italian architettura barocca (Baroque architecture) is especially renowned for its theatricality, grandeur, and dynamism. Buildings are often adorned with colonne tortili (twisted columns), volte affrescate (frescoed vaults), and complex facciate (façades) that seem to ripple with movement. Rome, as the heart of the Catholic world, became the epicenter of this style, with masterpieces such as San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane and Sant’Agnese in Agone, designed by architects like Borromini and Bernini. Their work sought to create an emotional experience through space, light, and form, with a clear goal of engaging both the mind and the senses. Bernini’s Baldacchino (canopy) in San Pietro (St. Peter’s Basilica) is a quintessential example, blending architecture and sculpture in a dynamic and symbolic gesture of divine power.

In painting, the pittura barocca (Baroque painting) was characterized by intense contrasts of light and shadow, known as chiaroscuro, as well as emotionally charged subjects and compositions. Artists like Caravaggio revolutionized the visual arts with their realism, capturing human emotion in all its rawness. Their use of luce drammatica (dramatic light) and dynamic diagonals drew the viewer into the scene, creating a sense of immediacy and tension.

Music during the periodo barocco (Baroque period) also flourished in Italy, with composers such as Vivaldi, Corelli, and Monteverdi pushing the boundaries of musical expression. The invention of new forms like the concerto grosso (grand concerto) and the opera (opera) offered platforms for emotional storytelling and technical virtuosity. The focus on espressione emotiva (emotional expression) and ornate musical lines mirrored the visual extravagance of the period.

Ultimately, il barocco italiano (Italian Baroque) was a cultural expression of power, passion, and persuasion. Whether in the soaring dome of a church, the trembling figure of a saint in marble, or the crescendo of a violin concerto, the baroque spirit continues to evoke wonder, revealing the deep interconnection between art, belief, and society in Italy’s Golden Age.

BURRATA

Burrata (burrata cheese) is one of the most luxurious and beloved cheeses in Italian cuisine, known for its soft outer shell and creamy, delicate center. Originating from the region of Puglia (Apulia), in the southeastern part of Italy, burrata is a striking example of how Italian artisans transform simple ingredients into something truly extraordinary. Made from fresh latte di mucca (cow’s milk), it resembles a pouch of mozzarella (mozzarella cheese), but when cut open, it reveals a heart of stracciatella (shredded cheese and cream) that flows out with irresistible richness. The outer layer is crafted from stretched mozzarella curd, while the filling is a mixture of mozzarella strands and panna fresca (fresh cream), giving the cheese a contrast in textures and an indulgent flavor profile.

Traditionally, burrata was a clever solution for using up leftover curds from mozzarella production. It was invented by farmers who wanted to preserve their cheese using local methods, wrapping the cheese in foglie di asfodelo (asphodel leaves) which would indicate its freshness by changing color as it aged. Though this rustic technique is rarely used today, the attention to quality and freshness remains at the core of burrata production. Unlike aged cheeses, burrata must be consumed within a few days of being made. It is typically enjoyed at temperatura ambiente (room temperature) to allow the flavors to fully bloom and the texture to reach its optimal creaminess.

The flavor of burrata is gentle, milky, and slightly tangy, with the stracciatella inside providing a luxurious mouthfeel. It is often served as an antipasto (starter dish), accompanied by pomodori freschi (fresh tomatoes), olio extravergine di oliva (extra virgin olive oil), and basilico (basil), forming a dish that celebrates the purity of Italian ingredients. Chefs also pair it with prosciutto crudo (cured ham), carpaccio di manzo (beef carpaccio), or even frutta di stagione (seasonal fruit) to highlight its versatility. Despite its delicate nature, burrata stands out in any dish because of its richness and visual appeal.

Though originally a specialty of Puglia, burrata has become popular across Italy and the world, often featured in upscale restaurants and gourmet shops. However, nothing compares to tasting a freshly made burrata artigianale (artisan burrata) near the farms where it was born. Its short shelf life and need for careful handling make it a symbol of the Italian philosophy of respecting freshness, craftsmanship, and simplicity. Every bite of burrata carries with it the sun-drenched fields of southern Italy and the passion of the artisans who continue to make it by hand.

CAMPANILE

The campanile (bell tower) is one of the most iconic and defining features of the Italian architectural landscape, rising proudly above cities, towns, and villages across the country. Derived from the Latin word campana (bell), the campanile serves both a practical and symbolic role in Italian life. Traditionally, it houses campane (bells) that ring to mark time, call the faithful to messa (mass), and announce significant events such as weddings, funerals, or communal festivals. Though often associated with churches, campanili (bell towers) are also found in piazze (public squares), where they stand as civic landmarks and symbols of local identity. The architectural styles of these towers vary by region and period, ranging from the slender and elegant Gothic spires of northern Italy to the more solid and square torri romaniche (Romanesque towers) of central and southern Italy.

One of the most famous examples is the Campanile di San Marco (St. Mark's Bell Tower) in Venezia (Venice), a towering structure that dominates the Piazza San Marco and has guided ships into the lagoon for centuries. Equally well known is the Torre Pendente di Pisa (Leaning Tower of Pisa), which, despite its unintended tilt, functions as the campanile for the nearby duomo (cathedral). These structures are not only engineering feats but also carry deep cultural and spiritual meaning. They reflect the Italian love of beauty, harmony, and proportion, as well as the importance of sound in communal life. The ringing of the campane punctuates the day in Italian towns, creating a rhythm that connects the present to centuries of tradition.

Many campanili are separate from the churches they serve, allowing for greater flexibility in design and often giving the impression of a torre indipendente (independent tower). This detachment allows the tower to stand out as a sculptural element, contributing to the unique silhouette of each centro storico (historic center). Inside, narrow scale a chiocciola (spiral staircases) lead to the top, where visitors are rewarded with panoramic views of the surrounding countryside or cityscape.

The campanile is more than a structure; it is a testament to Italian history, craftsmanship, and communal life. Built in stone, brick, or marble, decorated with merli (battlements), bifore (twin-arched windows), or logge (arcaded galleries), these towers rise like sentinels over the landscape, bearing witness to the passage of time. Whether rising beside a grand cathedral or standing alone in a rural borgo (village), the campanile embodies the voice and memory of Italy, echoing through the centuries.

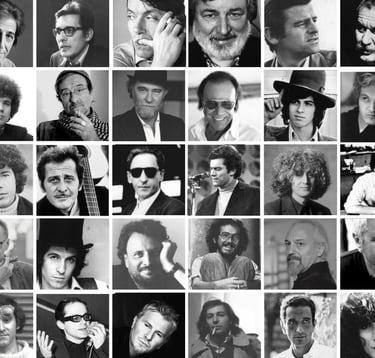

CANTAUTORE

The cantautore (singer-songwriter) holds a special place in Italian culture, blending poetry, music, and social commentary into a unique and deeply respected art form. Unlike commercial pop artists, the cantautore is both the author of the testo (lyrics) and the musica (music), crafting songs that often reflect personal experiences, political ideas, or philosophical reflections. This tradition gained prominence in the 1960s and 1970s, during a time of great cultural and political transformation in Italy, and has since remained a vital voice in the nation’s artistic landscape. The figure of the cantautore is not just a musician but a modern-day poeta (poet), someone who uses melody as a vehicle for meaning, emotion, and critique.

Legends like Fabrizio De André, Lucio Dalla, Francesco Guccini, and Franco Battiato brought the genre to artistic heights, weaving narratives that spoke of love, war, alienation, spirituality, and justice. Their songs often transcend the limits of traditional music, incorporating elements of letteratura (literature), filosofia (philosophy), and even teatro (theater). A cantautore may perform with minimal accompaniment, such as an acustica (acoustic guitar), highlighting the power of words and voice over elaborate production.

The role of the cantautore is also deeply regional. Many sing in dialetto (dialect) or reference specific cities and cultural contexts, adding a layer of local identity to their work. Despite this, their themes are often universal, touching on human experience in a way that resonates across generations. A song by a cantautore is not just entertainment—it is a piece of impegno (social engagement), often reflecting concerns about the world, inequality, memory, and belonging.

Contemporary artists like Niccolò Fabi, Samuele Bersani, and Levante continue the legacy, bringing the sensibility of the cantautore into modern genres while remaining rooted in introspection and lyrical depth. Even mainstream pop has felt the influence of this tradition, with many artists adopting the storytelling and emotional nuance that characterize the cantautori (singer-songwriters).

In the Italian imagination, the cantautore remains a symbol of authenticity, intellect, and emotional truth. Whether singing in a small club (venue), at a major festival musicale (music festival), or through a crackling radio (radio), their voice carries more than melody—it carries the soul of Italian thought and feeling, bound by rhythm but elevated by meaning.

CANTINA

In Italy, the word cantina (wine cellar) evokes much more than a storage space; it is the beating heart of the country’s enological traditions and a place where history, family, and craftsmanship converge. Tucked beneath farmhouses, sprawling estates, and even urban dwellings, the cantina shelters barrels of vino (wine) aging quietly in the cool, consistent embrace of stone walls. Here, the journey of mosto (must) transforms through fermentation, guided by the steady hand of the enologo (enologist) and the watchful eye of the viticoltore (vine grower). The atmosphere is thick with the earthy scent of oak, chestnut, or cherry botti (casks), each imparting unique character to the evolving liquid. Walking through a traditional cantina sotterranea (underground cellar), one might pass rows of barrique (small oak barrels), their surfaces chalk-marked with harvest years and grape varietals such as Sangiovese, Nebbiolo, or Greco.

Historically, the cantina served as a communal hub where neighbors gathered during vendemmia (grape harvest) to press grapes, share meals, and exchange stories while the new vintage began its slow maturation. In many regions, especially in Toscana (Tuscany) and Piemonte (Piedmont), families still maintain small, private cellars alongside modern cantine sociali (cooperative wineries), where producers pool resources to craft wines under a shared label. Inside these vaulted spaces, one finds tools like the torchio (wine press) and the damigiana (demijohn), glass orbs once used for transporting young wine to nearby villages. Despite technological progress, these instruments remind visitors of the intimate bond between the Italian people and their land.

Beyond wine, the cantina often doubles as a pantry for salumi (cured meats), formaggi (cheeses), and even jars of conserve (preserves), capturing the rhythm of seasonal abundance. In homes lacking a separate dispensa (larder), the cellar’s stable temperature provides the perfect environment for aging prosciutto or ripening caciocavallo. Thus, the cantina becomes a sensory archive, its shelves lined with flavors that narrate a household’s culinary legacy.

Modern oenotourism elevates the cantina to a destination in itself. Visitors can partake in degustazioni (tastings), swirling ruby liquid in crystal calici (glasses) while the cantiniere (cellar master) explains notes of frutta rossa (red fruit) or hints of spezie (spice). Some estates integrate architettura contemporanea (contemporary architecture) into their historic cellars, balancing innovation with respect for tradition. Whether ancient or avant-garde, the Italian cantina remains a sanctuary of craft, where each barrel, bottle, and brick tells a story of patience, terroir, and the enduring Italian devotion to the art of living well.

CAPPUCCINO

Cappuccino (cappuccino) is one of the most iconic symbols of Italian coffee culture, cherished both in Italy and around the world for its perfect balance of flavor, texture, and ritual. Composed of caffè espresso (espresso coffee), latte caldo (hot milk), and schiuma di latte (milk foam), the cappuccino is a harmonious blend that showcases the Italian mastery of coffee preparation. Typically served in a tazza bianca (white cup) of around 150 to 180 milliliters, the drink offers a velvety mouthfeel, a bold yet smooth flavor, and a delicate crown of foam that often invites artistic designs known as latte art (milk art).

The name cappuccino is said to originate from the Frati Cappuccini (Capuchin friars), a Franciscan order whose robes were a distinctive brown color. The mix of coffee and milk in the cup resembles this hue, hence the name. But beyond its visual appeal, the cappuccino holds a specific place in Italian daily life. It is traditionally consumed only in the mattina (morning), often with a cornetto (croissant) at the local bar (café). Ordering one after mezzogiorno (noon) is generally seen as unusual in Italy, where the pairing of milk and coffee is associated with breakfast and is thought to be too heavy for later in the day.

Making a proper cappuccino requires skill. The barista (barista) begins with a well-extracted espresso (espresso), a small but powerful shot that forms the foundation. Then comes the steamed milk, frothed to a creamy consistency and carefully poured to create a layered structure with a thin layer of fine foam on top. Unlike a latte, which contains more milk and less foam, or a macchiato, which is simply espresso “stained” with milk, the cappuccino strikes a perfect balance among its components.

Across Italy, each region may interpret the cappuccino slightly differently. Some prefer it with cacao spolverato (dusting of cocoa powder), others with a thicker layer of foam. Still, the unspoken rules of cultura del caffè (coffee culture) remain remarkably consistent: the cappuccino is not just a drink, but a ritual, a signal that the day has begun. In the bustling environment of an Italian bar, locals sip their cappuccinos standing at the counter, engaging in brief exchanges with the barista and fellow customers, creating a moment of connection before the day’s activities begin.

While the cappuccino has been embraced and reinterpreted worldwide—often in larger sizes and with various toppings—the essence of the Italian cappuccino lies in its simplicity, quality, and timing. It is a daily act of self-care, a small but significant pleasure that reflects the Italian belief in savoring life’s moments, one cup at a time.

CARABINIERI

The Carabinieri (Carabinieri Corps) are one of the most recognizable and respected institutions in Italy, serving as both a forza di polizia (police force) and a forza armata (military force). Officially known as the Arma dei Carabinieri (Carabinieri Corps of the Army), they play a unique dual role that blends civil law enforcement with national defense responsibilities. Founded in 1814 by Vittorio Emanuele I (Victor Emmanuel I) of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Carabinieri have evolved into a central pillar of Italian security and identity. Their name comes from the word carabina (carbine), a short rifle they historically carried.

Dressed in their iconic uniforme blu scuro con bande rosse (dark blue uniforms with red stripes), the Carabinieri are easily identifiable throughout Italy. They are often seen patrolling piazze (squares), strade principali (main streets), and aree rurali (rural areas), ensuring public safety and maintaining ordine pubblico (public order). Unlike the Polizia di Stato (State Police), which operates under the Ministry of the Interior, the Carabinieri report to both the Ministero della Difesa (Ministry of Defense) and the Ministero dell’Interno (Ministry of the Interior), depending on their role and assignment.

One of their most important functions is criminal investigation. The Carabinieri operate as a polizia giudiziaria (judicial police), conducting investigations, arresting suspects, and collaborating with magistrates. Specialized units such as the ROS (Special Operations Group) tackle organized crime, terrorism, and high-profile criminal cases, while the NAS (Anti-Adulteration and Health Unit) focuses on food safety, counterfeit goods, and health violations. They are also entrusted with the protection of cultural heritage through the TPC (Cultural Heritage Protection Unit), recovering stolen art and antiquities from museums, churches, and archaeological sites.

In addition to their policing duties, the Carabinieri also serve in international missions under the auspices of the ONU (UN), NATO, and the Unione Europea (European Union), helping to stabilize conflict zones and train local forces. Their training, discipline, and reputation for integrity have made them respected representatives of Italian values abroad.

The Carabinieri are also embedded in Italian popular culture. From TV series and novels to songs and jokes, they are both admired and affectionately parodied. Their motto, "Nei secoli fedele" (Faithful through the centuries), speaks to their enduring role in Italian life—not just as law enforcers, but as guardians of tradition, community, and the rule of law. Whether directing traffic in a small paese (village) or investigating mafia crimes in a major città (city), the Carabinieri remain a symbol of authority, service, and national pride.

CANNOLI

Cannoli are among the most iconic dolci (sweets) of Italian gastronomy, deeply rooted in the culinary and cultural traditions of Sicily. Instantly recognizable by their crisp, tubular shell and creamy filling, cannoli embody the balance between texture, flavor, and craftsmanship that defines much of Italian pastry-making. Though today they are enjoyed across Italy and far beyond its borders, cannoli originated as a regional specialty closely tied to Sicilian history, local ingredients, and festive customs.

Traditionally, cannoli consist of a fried pastry shell made from a dough enriched with sugar, flour, and sometimes cacao or marsala wine, which gives the shell its distinctive aroma and dark golden color. The shell is filled with a smooth cream of ricotta (fresh sheep’s milk cheese), sweetened with sugar and often enhanced with canditi (candied fruit), gocce di cioccolato (chocolate chips), or scorza d’arancia (orange peel). The contrast between the crunchy exterior and the soft, delicate filling is central to the cannolo’s appeal and must be carefully preserved by filling the pastry only shortly before serving.

The origins of cannoli are commonly linked to the Arab presence in Sicily between the 9th and 11th centuries, a period that profoundly influenced the island’s cuisine. Ingredients such as sugar, citrus fruits, and almonds were introduced or popularized during this time, shaping many classic Sicilian desserts. Cannoli are traditionally associated with Carnevale (Carnival), a time of abundance and indulgence before Lent, though today they are enjoyed year-round in pasticcerie (pastry shops) and homes alike.

Over time, regional variations have developed. In western Sicily, particularly around Palermo, cannoli are often larger and richly filled, while in eastern areas they may be smaller and more delicately decorated. Some versions feature pistacchio di Bronte (pistachio from Bronte), granella di nocciole (chopped hazelnuts), or even cherries and cinnamon, reflecting local tastes and ingredients.

Today, cannoli are a symbol of Sicilian identity and Italian culinary heritage. They appear in food literature, cinema, and popular culture, representing convivialità (conviviality) and the pleasure of sharing food with your love ones.

CASSATA

The cassata (cassata cake) is one of Sicily’s most emblematic desserts, a vibrant and decadent expression of the island’s complex cultural heritage. This traditional dolce siciliano (Sicilian dessert) is as much a visual feast as it is a culinary one, with its rich layers of flavor, ornate decorations, and centuries-old symbolism. The classic cassata is made with pan di Spagna (sponge cake), which is soaked in liquore (liqueur) or succo di agrumi (citrus juice), then layered with ricotta di pecora (sheep’s milk ricotta) blended with zucchero (sugar) and often mixed with gocce di cioccolato (chocolate chips) and canditi (candied fruit). It is then covered with a thin shell of pasta reale (marzipan), glazed with a sugary glassatura (icing), and topped with vibrant pieces of frutta candita (candied fruit), forming a colorful mosaic that reflects the Baroque spirit of Sicilian artistry.

The origins of the cassata date back to the periodo arabo (Arab period) in Sicily, around the 10th century, when ingredients such as sugar, citrus, almonds, and exotic spices were introduced to the island. The very name "cassata" may derive from the Arabic word qas'at (bowl), referring to the round shape in which the cake was originally molded. Over the centuries, the recipe evolved through successive cultural layers—Norman, Spanish, and French—each leaving its imprint on the final creation. By the time of the epoca barocca (Baroque era), the cassata had become a celebratory dessert, particularly associated with Pasqua (Easter) and festive occasions.

There are regional variations across Sicily. In Palermo, the cassata siciliana is elaborately decorated and served cold, while in the area around Catania, a baked version known as cassata al forno (baked cassata) omits the green marzipan and icing but retains the ricotta and chocolate filling inside a crust of pastry. Each version carries with it a strong sense of place, tradition, and ritual. In some towns, the preparation of cassata is passed down through generations, guarded as a family secret and performed with reverence during holidays or celebrazioni religiose (religious celebrations).

Beyond its sweetness, the cassata is a symbol of Sicilian resilience, abundance, and hospitality. Its ingredients tell the story of centuries of conquest and coexistence, while its flamboyant appearance captures the theatricality and sensuality of southern Italian culture. Whether served in a refined pastry shop in Palermo or in a humble kitchen in the Sicilian countryside, the cassata remains an edible work of art, a testament to Sicily’s extraordinary ability to transform history into flavor.

CONFETTI

Confetti (sugar-coated almonds) are an essential part of Italian celebratory traditions, especially in weddings, baptisms, and other life milestones. Unlike the English meaning of “confetti” as paper bits thrown in the air, in Italy, confetti refers to elegant mandorle (almonds) coated in a smooth, shiny layer of zucchero (sugar). These treats are not only delicious but rich in symbolism, representing the bittersweet nature of life’s most important transitions—joy tempered with challenge, sweetness with depth.

Traditionally, Italian confetti are made using whole almonds, often of the prized mandorla di Avola (Avola almond), known for its flat shape and refined flavor. The almond is repeatedly dipped in boiling sugar syrup and tumbled in a copper drum until a firm, glossy shell forms. The process, done by skilled artisans known as confettieri (confectioners), requires patience, precision, and a deep understanding of timing and temperature. The final result is a perfectly oval, crisp shell with a tender nut inside—a texture and flavor contrast that has delighted Italians for centuries.

Each color of confetto (single sugared almond) carries a different meaning. Bianco (white) is used for weddings and symbolizes purity and unity. Azzurro (blue) and rosa (pink) are for baptisms, depending on the child’s gender. Rosso (red) is reserved for graduations, symbolizing success and strength. Verde (green) is for engagements, giallo (yellow) for first communions, and argento (silver) or oro (gold) for 25th and 50th wedding anniversaries. These colors are typically wrapped in delicate tulle (tulle fabric) or satin, tied with ribbon, and given as bomboniere (favors) to guests as a thank-you and keepsake.

The town of Sulmona, in the Abruzzo region, is widely considered the historic capital of confetti production. Here, artisans have elevated the craft into art, shaping confetti into flowers, bouquets, and intricate decorations that are as beautiful as they are symbolic. The confetti di Sulmona have earned a place not only in Italian hearts but also in cultural tourism, with entire shops and festivals dedicated to their display and sale.

Over time, the world of confetti has expanded beyond the classic almond variety. Today, you can find versions filled with cioccolato (chocolate), pistacchio (pistachio), limone (lemon), and other flavors, catering to contemporary tastes while honoring traditional values. Whether enjoyed as a treat, displayed as decoration, or given as a gesture of affection, Italian confetti remain a sweet symbol of love, luck, and life’s most cherished moments.

CORNUTO

The word cornuto (cuckold) is a powerful and culturally loaded term in Italian, deeply rooted in centuries of social, emotional, and even folkloric significance. Literally meaning "horned," cornuto refers to a man whose partner—usually his wife—has been unfaithful. The "horns" are metaphorical and symbolize the humiliation of being betrayed, especially without knowing it. In Italian culture, the idea of being a cornuto carries not just the pain of infidelity but also a strong sense of public embarrassment and masculine dishonor.

The origins of the association between corna (horns) and infidelity go back to ancient times. In medieval Europe, horns were sometimes used as a public symbol of shame or mockery. In Italy, this evolved into a gesture and a word used to insult or joke about someone suspected of being cheated on. The hand gesture of fare le corna (making the horns with the index and little finger extended) can either be a way to ward off bad luck—or a crude way to accuse someone of being a cornuto behind their back. This duality—between superstition and insult—is a perfect reflection of the word’s emotional charge.

Being called a cornuto is one of the strongest insults in informal Italian, especially in the south. It's not uncommon to hear exclamations like "Cornuto e bastardo!" (Cuckold and bastard!) shouted during heated arguments or in traffic disputes. The idea isn’t always literal—it can also be used to shame someone perceived as weak, naïve, or easily manipulated. Because of this, accusations of cornutaggine (being a cuckold) have long fueled both street fights and comedic routines in Italian culture.

Interestingly, Italian comedy and theater often play with the concept of cornuto in humorous ways. The classic character of the jealous husband, obsessively suspicious or hilariously clueless, appears frequently in commedia all’italiana (Italian-style comedy) and teatro napoletano (Neapolitan theater). Here, the cornuto becomes both victim and fool, someone to laugh at but also pity. Even in opera, literature, and folk songs, the figure of the cornuto surfaces with tragic or comic overtones, highlighting the depth of its cultural resonance.

In modern times, while the term may be used more ironically among friends, it remains deeply offensive when taken seriously. Calling someone a cornuto touches on personal pride, relationships, and public image—three things Italians hold very dear. As such, it's a word to understand and approach with caution, carrying centuries of cultural baggage in just three syllables.

DOLCE VITA

Dolce vita (sweet life) is one of the most iconic expressions in the Italian language, evoking a vision of leisurely pleasure, effortless elegance, and a joyful embrace of beauty and indulgence. The phrase gained global fame through Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita, a cinematic masterpiece that both celebrated and critiqued the hedonistic lifestyle of post-war Rome’s elite. Since then, dolce vita has come to symbolize an entire cultural attitude—one rooted in the art of savoring life, of finding sweetness not just in luxury, but in everyday moments.

At its core, dolce vita is about a certain leggiadria (gracefulness) in how one lives. It might mean sipping a perfectly crafted cappuccino (cappuccino) at a sunlit piazza (square), strolling along the Lungotevere (Tiber River promenade) at dusk, or sharing a long, laughter-filled dinner with friends over vino rosso (red wine) and pasta fresca (fresh pasta). It’s not about extravagance in the material sense—though fashion, art, and beauty play key roles—but about prioritizing tempo per sé (time for oneself) and cultivating a life filled with sensory pleasure, aesthetic appreciation, and human connection.

Historically, the notion of dolce vita emerged during the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, when Italy transitioned from wartime hardship to prosperity. This was the era of Vespa scooters, Cinecittà (Rome’s film studios), and international stars like Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni, who made the Roman lifestyle seem effortlessly chic. The Via Veneto in Rome became the symbolic heart of the dolce vita, where artists, celebrities, and paparazzi mingled in a glamorous swirl of fashion, scandal, and charm.

But beyond its historical moment, dolce vita expresses something timeless in the Italian soul: a refusal to rush, a love for piaceri semplici (simple pleasures), and an ability to turn even routine acts—eating, talking, dressing—into expressions of art. It’s seen in the pride Italians take in their cucina (cuisine), in the elegance of everyday fashion, in the ritual of fare la passeggiata (taking a walk) after dinner. It's the opposite of efficiency-for-efficiency’s-sake; it's about presence, warmth, and beauty.

Today, dolce vita continues to inspire people around the world who seek to escape stress and speed, and instead embrace a life that feels rich, full, and joyously unhurried. It reminds us that pleasure is not a luxury, but a right—and that the truly good life is made not of possessions, but of moments savored deeply and shared generously.

FESTA PATRONALE

A festa patronale (patron saint festival) is one of the most cherished and vibrant expressions of local identity in Italian culture. Celebrated in towns and villages across Italy, a festa patronale honors the santo patrono (patron saint) who is believed to protect and watch over the community. These festivals are a blend of devozione religiosa (religious devotion), tradizione popolare (popular tradition), and festa collettiva (collective celebration), creating a unique atmosphere where sacred and secular intertwine.

Each Italian town has its own santo protettore (protective saint), and the day dedicated to this saint is marked on the local calendar as a time for both spiritual observance and joyous gathering. The celebration typically begins with a messa solenne (solemn mass) in the local chiesa madre (main church), often followed by a processione (procession) in which a statue or relic of the saint is paraded through the streets, accompanied by hymns, prayers, and bande musicali (marching bands). Locals dress in traditional attire or formal clothes, and the entire town participates with a deep sense of pride and belonging.

But a festa patronale is far more than just a religious event. It is also a moment of community renewal, marked by mercatini (street markets), giostre (carnival rides), spettacoli pirotecnici (fireworks displays), and concerti dal vivo (live concerts). Local food plays a starring role—porchetta (roast pork), arrosticini (grilled lamb skewers), zeppole (fried dough pastries), and countless other regional specialties are prepared and shared in stand gastronomici (food stands) or outdoor feasts. For many, it is also a time for families to reunite, for emigrants to return home, and for young people to meet and celebrate under the summer sky.

The atmosphere during a festa patronale is one of emotional intensity and joyful noise, with streets decorated in luminarie (festive lights) and voices rising in song or cheers. In smaller villages, the sindaco (mayor) may give a speech, and awards might be given for contributions to community life. The mix of sacro e profano (sacred and profane) gives these festivals a distinctively Italian flavor: reverent yet playful, devout yet deeply human.

Whether held in a small paese di montagna (mountain village) or a large coastal city, a festa patronale is more than a date on the calendar—it is a living tradition that unites past and present, spirit and spectacle, faith and festivity. It reaffirms a shared cultural identity rooted in place, memory, and celebration, and reminds Italians of their enduring connection to their territorio (homeland), their saints, and each other.

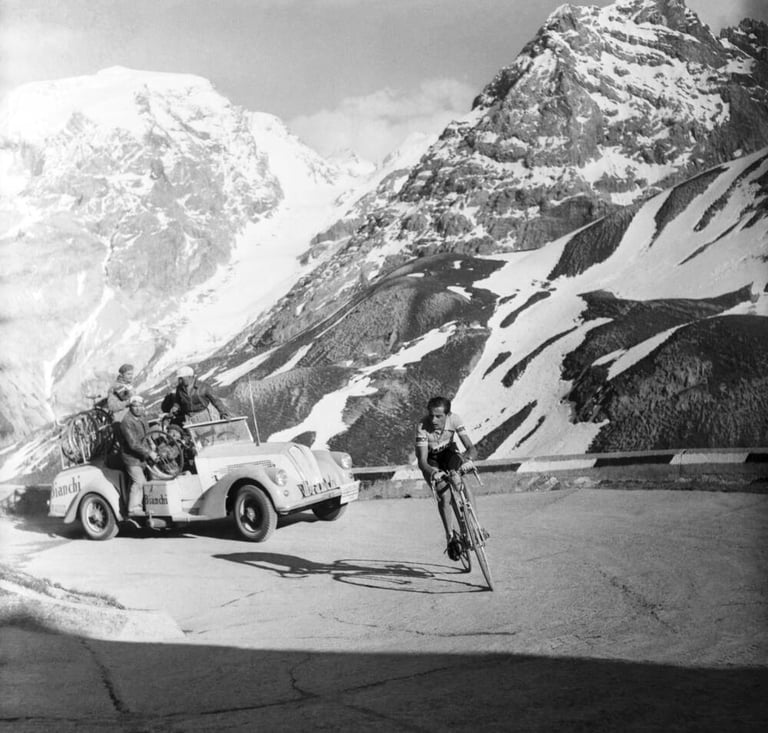

GIRO D’ITALIA

The Giro d’Italia (Tour of Italy) is one of the most prestigious and beloved sporting events in the world, a legendary corsa ciclistica (cycling race) that weaves through the heart and soul of the Italian landscape. First held in 1909, the Giro has grown into a grand, multi-stage competition that spans over three weeks each spring, drawing elite cyclists from around the globe and captivating millions of fans with its dramatic climbs, thrilling sprints, and breathtaking views of Italy’s diverse geography.

More than a mere race, the Giro d’Italia is a national ritual, rich with symbolism and spectacle. Riders compete for the coveted maglia rosa (pink jersey), awarded to the overall leader of the race. The color pink was chosen to match the pages of La Gazzetta dello Sport, the Italian sports newspaper that founded the event. Other jerseys include the maglia ciclamino (cyclamen jersey) for the best sprinter, the maglia azzurra (blue jersey) for the best climber, and the maglia bianca (white jersey) for the best young rider, each reflecting a different facet of cycling prowess.

The Giro is famous for its grueling tappe di montagna (mountain stages) through the Alpi (Alps) and Appennini (Apennines), where legendary ascents like the Passo dello Stelvio (Stelvio Pass) and Monte Zoncolan (Zoncolan Mountain) test the limits of human endurance. These dramatic climbs, often in snow-capped conditions, are where champions are made and legends born. Equally captivating are the tappe cittadine (urban stages) that pass through historic towns, winding through centri storici (historic centers) and across piazze affollate (crowded squares), bringing the race into direct contact with Italy’s cultural heritage.

The Giro d’Italia is also a celebration of Italian identity and unity. Each year, the route changes, highlighting different regioni (regions) and offering a panoramic journey through the country’s geography, from the coste mediterranee (Mediterranean coasts) to the colline toscane (Tuscan hills), from the laghi del nord (northern lakes) to the pianure della Pianura Padana (Po Valley plains). Along the way, the race showcases the architecture, food, dialects, and local pride of the communities it passes through, turning the entire nation into a living stage.

For many Italians, the Giro is not just a sporting event but a part of their cultural DNA. Families gather around the television or line the streets to cheer, wave flags, and celebrate the passage of the carovana rosa (pink caravan)—the parade of support vehicles, sponsors, and festivities that travels with the race. It is a spectacle of color, motion, and emotion, where athleticism meets storytelling, and every rider becomes a character in an epic unfolding across Italy’s roads.

In the global world of professional cycling, the Giro d’Italia stands alongside the Tour de France and Vuelta a España as one of the three Grand Tours, but many consider it the most poetic, the most unpredictable, and the most Italian. It is a race of beauty and brutality, tradition and transformation—a rolling homage to the spirit of a nation that rides on two wheels but dreams without limits.

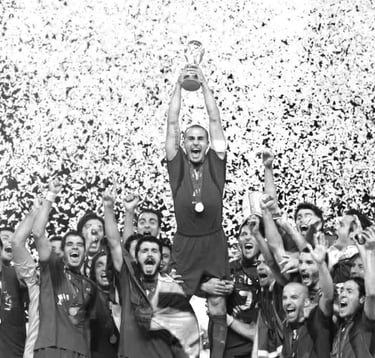

AZZURRI

Azzurri (the blues) is the iconic nickname for Italy’s national sports teams, especially the nazionale di calcio (national football team), and it holds a special place in the hearts of Italians. The term comes from the color azzurro Savoia (Savoy blue), a shade of light royal blue historically associated with the Casa Savoia (House of Savoy), the royal dynasty that unified Italy in the 19th century. Though Italy became a republic in 1946, the color remained as a unifying national symbol, proudly worn by athletes representing the country on the global stage.

When Italians refer to the Azzurri, they are often speaking of the men’s football team, whose legendary history is filled with triumphs, heartbreaks, and unforgettable moments. The maglia azzurra (blue jersey) has become a symbol of national pride and emotional intensity. Victories in the Coppa del Mondo (World Cup)—particularly in 1934, 1938, 1982, and 2006—have etched the name Azzurri into global football history. Each tournament stirs powerful collective emotions, from the tears of victory to the silence of defeat, uniting the nation in a shared experience that transcends sport.

But the term Azzurri is not limited to football. It applies to all Italian national teams that wear the blue jersey: the Azzurri del rugby (rugby team), the Azzurri del basket (basketball team), the Azzurri dell’atletica (track and field team), and even the Azzurre (the female blues), who proudly represent Italy in women’s competitions. The name carries with it a sense of elite representation, discipline, and the weight of centuries of culture and expectation.

Wearing the maglia azzurra is seen as an honor that goes beyond athletic achievement. It represents a connection to history, to family traditions of watching games together, and to a larger Italian identity that celebrates not just winning, but grinta (grit), spirito di squadra (team spirit), and passione (passion). The blue color has become so embedded in the national consciousness that it's often used as shorthand in headlines and everyday speech, as in "Forza Azzurri!" (Go Blues!), shouted from windows and televisions during major tournaments.

Whether under the summer sun of a European championship or beneath the winter lights of the Olympics, the Azzurri embody the spirit of a people who compete with heart, pride, and elegance. They are more than athletes—they are symbols of what it means to be Italian on the world stage: proud, stylish, emotional, and fiercely united under the banner of blue.

MAIOLICA

Maiolica (majolica) is one of Italy’s most celebrated ceramic traditions, renowned for its brilliantly colored, tin-glazed pottery that turns everyday objects into works of art. This decorative technique, which reached its peak during the Rinascimento (Renaissance), is instantly recognizable by its glossy white background and vivid hand-painted motifs, ranging from motivi floreali (floral patterns) and scene mitologiche (mythological scenes) to stemmi araldici (heraldic crests) and ritratti rinascimentali (Renaissance portraits). The name maiolica is thought to derive from Maiorca (Majorca), the Mediterranean island that was a key hub in the trade of Islamic ceramics to Italy in the Middle Ages.

The technique involves coating earthenware with a layer of smalto bianco opaco (opaque white glaze), which serves as a perfect canvas for colorful decoration. Once painted, the piece is fired again, fusing the glaze and colors into a luminous, durable surface. What sets maiolica apart is not only its technical brilliance, but also its ability to fuse utility and beauty—plates, bowls, vases, tiles, and albarelli (apothecary jars) become both functional and ornamental.

Italy’s most famous centri di produzione (production centers) for maiolica include Deruta, Faenza, Urbino, and Castelli, each with its own distinctive style and decorative vocabulary. In Faenza, for example, geometric and floral designs dominate, while Urbino became known for istoriato ware—narrative scenes drawn from classical mythology and history, often as detailed as paintings. The word faience, used in French and English to describe glazed pottery, actually comes from Faenza, underlining the town’s influence on European ceramics.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, maiolica became a symbol of status and sophistication among Italian nobility and wealthy merchants. Elaborately painted pieces were given as regali di nozze (wedding gifts), used to adorn palace interiors, or presented as diplomatic offerings. The themes depicted often reflected humanist ideals, classical learning, and the vibrant intellectual life of the Renaissance courts.

Today, maiolica remains a living art form in Italy. Skilled artigiani ceramisti (ceramic artisans) continue to produce hand-painted pieces using traditional methods passed down over centuries. Whether sold in boutiques, displayed in museums, or used at Italian dinner tables, maiolica still evokes a sense of heritage, craftsmanship, and timeless elegance.

More than just pottery, maiolica represents Italy’s enduring ability to transform the everyday into something sublime—where a bowl is not just a vessel, but a celebration of beauty, history, and artistic imagination baked into clay and fire.

MURANO

Vetro di Murano (Murano glass) is one of Italy’s most exquisite and time-honored artisanal traditions, originating from the island of Murano, a small cluster of islands in the Laguna Veneziana (Venetian Lagoon) just north of Venice. Renowned worldwide for its elegance, innovation, and extraordinary craftsmanship, vetro di Murano is more than just decorative glass—it is a symbol of Venetian artistic mastery and centuries of cultural heritage preserved in the fire of the furnace.

The history of vetro di Murano stretches back to the late 13th century, when the Repubblica di Venezia (Republic of Venice) ordered all glassmakers to move their furnaces to Murano in order to reduce the risk of fires in Venice’s wooden buildings and to protect the secrets of the craft. Over time, Murano became a tightly guarded center of excellence, where maestri vetrai (master glassmakers) developed and refined techniques that transformed glassmaking into an art form. These techniques included soffiatura (glassblowing), filigrana (filigree), murrine (mosaic glass), and incamiciato (cased glass), each producing distinct textures, colors, and forms that remain unique to Murano.

One of the defining features of Murano glass is its astonishing varietà cromatica (color variety), achieved through precise chemical formulas and metallic oxides added during the melting process. The glowing richness of blues, reds, greens, and golds has made Murano creations highly sought after for centuries. Glass objects range from intricate lampadari (chandeliers) and specchi decorati (decorative mirrors) to delicate perle di vetro (glass beads) and sculptural oggetti d’arte (art pieces), each piece individually handcrafted with a level of artistry that resists industrial imitation.

Throughout history, vetro di Murano was prized by royalty and nobility across Europe and the Ottoman Empire. It adorned the palaces of dogi (doges), embellished religious sanctuaries, and even served as diplomatic gifts from the Serenissima (Most Serene Republic) to foreign courts. The fame of Murano’s glassmakers grew so great that their knowledge was jealously guarded—glassmasters were prohibited from leaving the island, under threat of severe punishment, to protect trade secrets from foreign competitors.

Today, the tradition of vetro di Murano lives on in the furnaces and ateliers scattered across the island. While modern designers collaborate with historic fornaci (glass furnaces) to produce contemporary works, the commitment to manual production and artistic integrity remains unchanged. Each piece bears the mark of individuality—no two Murano glass creations are ever identical, and each carries with it the soul of the artisan who shaped it.

To hold or admire a piece of vetro di Murano is to encounter centuries of Venetian history, where glass is not just a material, but a medium of beauty, storytelling, and craftsmanship passed down through generations. It is one of the purest expressions of Italian artistic genius, shining with the same luminous spirit that has defined Venice for over 700 years.

NEOREALISMO

Neorealismo (neorealism) is one of the most influential movements in Italian cultural history, emerging in the aftermath of World War II as a powerful artistic response to the devastation, poverty, and disillusionment that gripped the country. Rooted primarily in cinema italiano (Italian cinema), neorealismo sought to strip away the artificial glamour and escapism of pre-war films and instead present the raw, unvarnished truth of everyday life—particularly the struggles of the classe operaia (working class), the disoccupati (unemployed), and the emarginati (marginalized).

The movement was deeply connected to the broader socio-political landscape of Italia del dopoguerra (postwar Italy), a nation grappling with the collapse of fascism, economic hardship, and the psychological trauma of war. Against this backdrop, registi neorealisti (neorealist directors) like Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Luchino Visconti began creating films that were revolutionary in both form and content. They used attori non professionisti (non-professional actors), shot on location reale (real locations) rather than in studios, and focused on stories that reflected the dignity, pain, and resilience of ordinary people.

One of the most iconic films of the movement is Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) by De Sica, a heart-wrenching portrayal of a father and son searching for a stolen bicycle in the streets of Rome—a seemingly simple premise that becomes a powerful allegory for hope and desperation in a fractured society. Another cornerstone is Rossellini’s Roma città aperta (Rome, Open City), filmed in the ruins of Nazi-occupied Rome, blending documentary-style realism with emotional intensity and political urgency.

Neorealism was not just a cinematic style; it was a cultural philosophy. It embraced sobrietà estetica (aesthetic sobriety), narrativa minimale (minimalist storytelling), and a focus on verità emotiva (emotional truth), rejecting melodrama in favor of authenticity. The movement had a profound influence on later global filmmakers, inspiring the French New Wave, British kitchen-sink dramas, and American independent cinema. Directors like Jean-Luc Godard, Ken Loach, and Martin Scorsese have all acknowledged their debt to neorealismo italiano.

Though the movement began to fade in the 1950s as Italy entered an era of economic growth and mass consumerism, its legacy continues to shape Italian film and cultural identity. Modern auteurs like Nanni Moretti, Matteo Garrone, and Alice Rohrwacher echo neorealist principles by focusing on realtà sociale (social reality), marginalità (marginality), and the tension between tradition and modernity.

In the broader scope of Italian history, neorealismo remains a defining moment—an artistic mirror held up to a wounded nation, capturing with brutal honesty and lyrical compassion the complex, painful rebirth of a people. It stands as a testament to the power of cinema not just to entertain, but to bear witness, provoke thought, and inspire change.

OLIO EXTRAVERGINE

Olio vergine di oliva (virgin olive oil) is one of the most prized and ancient staples of Italian cuisine and culture, a golden liquid that flows through the heart of Mediterranean life. Unlike olio extravergine di oliva (extra virgin olive oil), which must meet the strictest standards in terms of acidity and flavor, olio vergine is slightly less refined but still made solely by processi meccanici (mechanical processes) without the use of heat or chemicals. It retains much of the gusto fruttato (fruity taste) and aroma intenso (intense aroma) of the olive, though it may have a slightly higher level of acidità libera (free acidity)—usually between 0.8% and 2%.

In Italy, the production of olio vergine di oliva is not merely a process but a deeply rooted tradition, passed down from generazioni di olivicoltori (generations of olive growers), especially in regions like Toscana (Tuscany), Puglia, Umbria, and Sicilia (Sicily). The olives are typically harvested between October and December, either by hand or using mechanical shakers, and immediately pressed in frantoi (olive mills) to preserve the freshness and quality of the oil.

What distinguishes olio vergine from its extra virgin counterpart is its slightly more marcato sapore amaro (pronounced bitter flavor) and note più robuste (more robust notes), which some palates may actually prefer, especially for fritture leggere (light frying) or condimenti rustici (rustic dressings). While it may not carry the same marketing prestige as extravergine, olio vergine remains a prodotto naturale (natural product) that retains the beneficial properties of olives, including antiossidanti (antioxidants), vitamina E, and grassi monoinsaturi (monounsaturated fats) that contribute to salute cardiovascolare (cardiovascular health).

In Italian kitchens, olio vergine di oliva is valued for its versatility. It can be drizzled over verdure grigliate (grilled vegetables), used to enrich minestre e zuppe (soups and stews), or added to impasti per pane (bread dough) and piatti di pasta (pasta dishes). Its flavor is especially suited for piatti contadini (peasant-style dishes) that celebrate simplicity and authenticity.

Beyond its culinary uses, olio vergine di oliva has long been appreciated for its usi cosmetici e medicinali (cosmetic and medicinal uses). In ancient Rome, it was used to soften the skin, treat wounds, and even as a base for profumi artigianali (artisanal perfumes). Today, it remains a key ingredient in natural soaps and skincare, a reminder of its enduring presence in both daily life and wellness.

PANETTONE

Panettone is one of Italy’s most beloved and iconic desserts, a tall, dome-shaped sweet bread traditionally enjoyed during the feste natalizie (Christmas holidays). Originating from Milano (Milan), this rich, buttery delicacy is much more than just a seasonal treat—it is a symbol of Italian craftsmanship, celebration, and the art of pasticceria (pastry-making). What makes panettone truly special is its unique combination of impasto lievitato (leavened dough), ingredienti semplici (simple ingredients), and a processo di lievitazione lenta (slow leavening process) that can take several days to complete.

The dough of panettone is made with farina (flour), uova (eggs), zucchero (sugar), burro (butter), and lievito madre (natural yeast), which gives it its characteristic airy texture and fragrant aroma. What distinguishes it further are the inclusions of uvetta (raisins), scorza d’arancia candita (candied orange peel), and sometimes cedro candito (candied citron), creating a balance of sweetness, tartness, and richness in every bite. When baked, it forms a golden, fluffy interior with a slightly caramelized crust—soft, aromatic, and deeply satisfying.

According to legend, panettone was invented in the 15th century, when a young kitchen assistant at the court of the Duke of Milan improvised a dessert using leftover ingredients to save a ruined banquet. The result was so delicious it became known as “il pan del Toni” (Toni’s bread), eventually evolving into panettone. Whether this story is myth or truth, what is certain is that panettone became a staple of tradizione natalizia italiana (Italian Christmas tradition), symbolizing generosity, family, and warmth.

Over the centuries, panettone has transcended its regional origins and become a national and international product, often gifted during the holidays in beautifully wrapped boxes. Modern versions include variations with cioccolato (chocolate), creme spalmabili (spreadable creams), glassa alle mandorle (almond glaze), and even panettoni salati (savory panettones), though purists remain loyal to the classic recipe.

Serving panettone is a ritual in itself. It’s typically sliced vertically and enjoyed with vino dolce (sweet wine), spumante (sparkling wine), or a warm cup of caffè (coffee). Some families toast it lightly or pair it with mascarpone or zabaglione, enhancing its already rich profile with a creamy accompaniment.

Today, artisanal bakers and historic brands like Motta, Vergani, and Loison continue to uphold the legacy of panettone, while small family bakeries across Italy infuse it with local flair and creativity. Whether you enjoy it as a holiday centerpiece, a heartfelt gift, or a nostalgic indulgence, panettone remains a testament to the Italian love for gusto, qualità, and tradizione—a sweet bread with a soul, as timeless as Christmas itself.

PRESEPE

Presepe (nativity scene) is one of the most cherished and widespread traditions in Italian Christmas culture, a deeply symbolic and artistic representation of the birth of Jesus that goes far beyond simple decoration. Rooted in centuries of fede cristiana (Christian faith) and arte popolare (folk art), the presepe captures the spiritual essence of the Natale italiano (Italian Christmas), combining religious devotion with regional creativity and craftsmanship.

The tradition of the presepe began with San Francesco d’Assisi (Saint Francis of Assisi) in 1223, when he organized a live nativity in the town of Greccio to bring the story of the Natività (Nativity) closer to the people. This powerful gesture gave rise to a tradition that would soon spread throughout Italy and evolve into elaborate, hand-crafted displays known as presepi artistici (artistic nativity scenes), featuring not only the Sacra Famiglia (Holy Family)—Gesù Bambino (Baby Jesus), Maria (Mary), and Giuseppe (Joseph)—but also a rich cast of characters, settings, and everyday scenes from rural Italian life.

In regions such as Campania, particularly in Napoli (Naples), the presepe napoletano has become a cultural icon. These intricate displays, often housed in wooden cases or scenografie di sughero (cork landscapes), include pastori (figurines) representing shepherds, artisans, merchants, angels, and animals, as well as humorous or symbolic figures like the pescivendolo (fishmonger), the venditrice di frutta (fruit seller), and even contemporary celebrities or politicians. The blending of sacred and profane, of timeless mystery and daily life, is what gives the presepe napoletano its unique emotional and artistic power.

Each element of the presepe carries symbolic meaning. The bue e asinello (ox and donkey) represent humility and patience. The stella cometa (comet star) guides the Re Magi (Three Wise Men) to the manger, and the rustic grotta (grotto) or stalla (stable) evokes simplicity and divine grace found in the most humble of places. In many Italian homes, the Gesù Bambino is not placed in the manger until the night of Vigilia di Natale (Christmas Eve), and the Re Magi slowly approach until they arrive on Epifania (Epiphany), January 6th.

Building the presepe is often a family ritual, involving the careful unpacking of statuine (figurines), arranging miniature paesaggi (landscapes), and lighting up tiny lanterne (lanterns) to bring the scene to life. In towns across Italy, especially in Umbria, Puglia, and Trentino, public nativity scenes—some life-sized or even animated—are set up in piazzas, churches, and hillside grottos, drawing crowds with their beauty and reverence.

More than just a decorative tradition, the presepe represents a fusion of religione, arte, and identità italiana (Italian identity). It speaks of warmth, faith, family, and the enduring hope of renewal. Whether humble or elaborate, every presepe tells the same story: the miracle of light born in darkness, and the unbroken continuity of an Italian tradition that transforms homes and hearts every December.

PROLOCO

Pro Loco is a uniquely Italian institution that embodies the spirit of local pride, volunteerism, and cultural preservation. Found in towns and villages throughout Italy, a Pro Loco is a non-profit association dedicated to promoting and protecting the patrimonio culturale locale (local cultural heritage), organizing events, supporting tourism, and fostering a strong sense of community. The term Pro Loco comes from Latin, meaning "for the place," and that is exactly its mission—to work per il bene del territorio (for the good of the local area).

Each Pro Loco operates independently but often collaborates with comuni (municipalities), enti turistici (tourism boards), and regional organizations. These associations are typically staffed by volontari (volunteers)—locals who are deeply passionate about their hometown’s traditions, landscape, food, and history. They may include teachers, retirees, students, and professionals, all united by the desire to make their paese (village) or cittadina (small town) more vibrant and appreciated.

The activities of a Pro Loco are as varied as the Italian landscape. They organize sagre (food festivals), feste patronali (patron saint celebrations), mercatini (craft markets), historical re-enactments, eventi folkloristici (folkloric events), and percorsi enogastronomici (food and wine trails). They also play a key role in publishing brochures, running local uffici informazioni turistiche (tourist information offices), and maintaining archivi storici (historical archives) and musei locali (local museums).

For small towns, especially in rural or less-visited areas, the Pro Loco is often the main driving force behind valorizzazione del territorio (territorial promotion). Thanks to their efforts, tourists discover lesser-known treasures: a medieval borgo (village), a forgotten tradizione artigianale (craft tradition), or a scenic sentiero naturalistico (nature trail). In doing so, Pro Loco associations help combat spopolamento (depopulation) and promote turismo sostenibile (sustainable tourism).

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Pro Loco phenomenon is its grassroots nature. These groups are not imposed from above but arise organically from the people themselves, often functioning as a modern form of piazza sociale (social square) where generations meet, collaborate, and celebrate their identità locale (local identity). Whether by preserving dialects, restoring churches, or simply organizing a Sunday lunch for the town square, the Pro Loco keeps the heart of Italy beating in its small communities.

Today, there are thousands of Pro Loco associations across Italy, coordinated nationally by UNPLI (Unione Nazionale delle Pro Loco d’Italia), ensuring their values are supported and their voices heard. In an era of globalization, the Pro Loco reminds Italians and visitors alike of the irreplaceable beauty of local traditions and the power of community spirit to preserve what matters most.

SALUMERIA

Salumeria (delicatessen) is an essential institution in Italian culinary culture, a shop dedicated to the sale of salumi (cured meats), cheeses, and a variety of high-quality food products that represent the soul of regional Italian gastronomy. Much more than a place to buy cold cuts, the salumeria is a temple of taste, tradition, and craftsmanship, where customers can find both everyday staples and gourmet delicacies. It combines the function of a butcher, a grocer, and a specialty food store—often with a personal touch that reflects generations of experience and passion.

The heart of any salumeria is its selection of salumi, a term that encompasses Italy’s vast and diverse array of cured pork products. These include prosciutto crudo (dry-cured ham), prosciutto cotto (cooked ham), mortadella (a large, seasoned pork sausage with fat cubes), salame (salami), coppa (cured neck meat), speck (smoked ham), lardo (cured pork fat), and pancetta (Italian bacon). Each product tells a story of tradizione artigianale (artisan tradition) and territorio (local origin), with protected designations such as DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) and IGP (Protected Geographical Indication) guaranteeing authenticity and quality.

But a salumeria offers much more than just meat. It often features an impressive selection of formaggi italiani (Italian cheeses) like parmigiano reggiano, pecorino romano, gorgonzola, asiago, and caciocavallo, stored carefully to preserve their flavor and texture. Many salumerie also sell prodotti sott’olio (vegetables preserved in oil), olive, pâté, pasta artigianale, conserve, sottaceti (pickles), and vini locali (local wines), turning each visit into a sensory experience.

A true salumiere (deli owner) is not just a vendor but a connoisseur and guide, often offering advice on pairings, slicing meats to the perfect thinness, and preparing panini farciti (stuffed sandwiches) on the spot with fresh pane croccante (crispy bread), formaggio cremoso (creamy cheese), and the best cuts available. Some salumerie even have small counters or tables where customers can enjoy spuntini (snacks) or degustazioni (tastings) on-site, blurring the line between shop and eatery.

Stepping into a traditional salumeria is like entering a microcosm of Italy itself—rich with aromas, textures, and the echoes of history. Whether in a bustling quartiere urbano (urban neighborhood) or a quiet paese di provincia (provincial town), the salumeria remains a cornerstone of Italian daily life and an ambassador of its culinary excellence. It is a celebration of simplicity, quality, and the enduring belief that good food is made with time, care, and a deep respect for tradition.

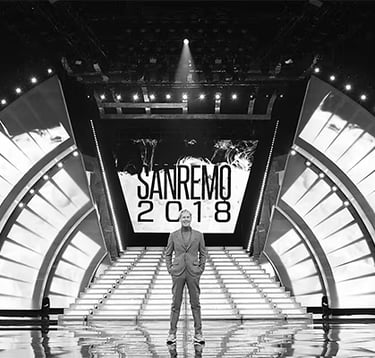

SANREMO

Festival di Sanremo (Sanremo Music Festival) is Italy’s most iconic and beloved musical event, an annual celebration of Italian song that has captivated audiences since its inception in 1951. Held in the seaside town of Sanremo, in Liguria, this multi-day competition has become a national ritual—combining music, glamour, and drama into a televised spectacle watched by millions across the country. More than just a music contest, the Festival di Sanremo is a mirror of Italian culture, society, and language, evolving with the times while remaining deeply rooted in tradition.

The stage of the Teatro Ariston (Ariston Theatre) is the heart of the festival, where established legends and emerging talents perform canzoni inedite (unpublished songs) before a live audience and a panel of juries. The performances range from heartfelt ballads and politically charged lyrics to comedic acts and bold experiments in pop, rock, and rap. Each artist competes for the coveted Leone d’Oro (Golden Lion) trophy, but the real prize is the cultural impact: many songs from Sanremo become instant classics, defining generations and entering the canon of musica leggera italiana (Italian popular music).

Over the decades, the Festival di Sanremo has launched the careers of countless stars, including Domenico Modugno, whose “Nel blu dipinto di blu” (Volare) became a global hit, as well as Laura Pausini, Eros Ramazzotti, Andrea Bocelli, and Il Volo. It has also served as a platform for bold statements and artistic freedom, with performances that reflect Italy’s shifting social and political climate.

What sets the festival apart is its unmistakable blend of artistry and spectacle. It’s not just about the music—it’s also about the conduttori (hosts), the ospiti internazionali (international guests), the monologhi (monologues), and the abiti scintillanti (sparkling outfits) that dominate headlines and social media for days. The Sanremo stage is a theater of emotion, where tears, controversy, laughter, and standing ovations are all part of the script.

Despite evolving formats and shifting musical tastes, the Festival di Sanremo retains its role as a unifying cultural moment. During festival week, Italy pauses to tune in. Families gather around the television, offices buzz with predictions and critiques, and newspapers dedicate pages to the classifica provvisoria (provisional rankings) and gossip di backstage (backstage gossip). The final night, traditionally on a Saturday, draws some of the year’s highest viewership ratings.

The winner of Sanremo often goes on to represent Italy in the Eurovision Song Contest, continuing the tradition of exporting Italian artistry to a global audience. Whether you love it, criticize it, or just can’t stop watching, the Festival di Sanremo is a yearly testament to the power of music, language, and national identity. In the words of its famous opening jingle: Perché Sanremo è Sanremo—because Sanremo is Sanremo.

SCIROCCO

Scirocco is the name Italians give to a hot, dry, and sometimes dust-filled wind that blows from the deserto del Sahara (Sahara Desert) across the Mediterranean and into southern Europe. Known for its intensity and distinctive qualities, the scirocco is more than a meteorological phenomenon—it is a presence that shapes landscapes, moods, and even cultural expressions in Italy, particularly in regions like Sicilia, Calabria, Puglia, and Sardegna.

The scirocco originates in the arid expanses of North Africa, where intense solar heating creates low-pressure systems that propel hot air masses northward. As this wind crosses the Mediterranean, it absorbs moisture, often becoming humid and oppressive by the time it reaches Italian shores. In coastal towns, the scirocco can blanket the air with a stifling stillness, carrying fine desert dust known as sabbia del deserto (desert sand) that clings to buildings, cars, and laundry lines. In the countryside, it can parch the earth and wither crops, while in the cities, it’s known to make tempers rise and sleep elusive.

In Italian culture and folklore, the scirocco has long been associated with psychological and emotional effects. People speak of it causing mal di testa (headaches), nervosismo (nervousness), and insonnia (insomnia). In older times, some even believed it could temporarily disturb the equilibrio mentale (mental balance), giving rise to the expression colpito dal scirocco—as if the wind itself could drive someone mad. This eerie quality has made it a frequent motif in literature and film, symbolizing tension, unrest, or an impending change in mood or fortune.

The scirocco also plays a key role in Italy’s microclimates. It can cause a sudden rise in temperatura (temperature), turning a cool spring day into a summer-like swelter. In mountainous areas, the wind’s warmth can trigger rapid scioglimento della neve (snowmelt), leading to flooding. In contrast, during winter months, the scirocco can bring rain-heavy clouds and grey skies, especially in central and northern Italy, where it sometimes collides with cooler air masses to form long periods of maltempo (bad weather).

Despite its inconveniences, the scirocco is an integral part of the Italian environment—a reminder of the country's geographical and cultural connection to both Europe and Africa. Its arrival is often marked with resignation and awe, as Italians prepare for days of heat, dust, and surreal stillness. Whether you’re watching palme piegate dal vento (palm trees bent by the wind) or experiencing the heavy, otherworldly silence it brings, encountering the scirocco is to feel a force that has shaped the Mediterranean world for millennia.

SCUDETTO

Scudetto (little shield) is one of the most iconic words in Italian sports culture, referring to the championship title awarded each year to the winning team of Serie A, the top tier of Italian football. The term derives from the small, tricolor shield—verde, bianco e rosso (green, white, and red)—that the victorious team earns the right to wear on their jerseys for the entire following season. This shield, shaped like a medieval crest, is more than a symbol of victory; it is a badge of honor, pride, and national identity.

The tradition of the scudetto dates back to 1924, when it was first introduced by Giorgio Vaccaro, a prominent figure in Italian football administration, to commemorate the reigning champion. Since then, lifting the scudetto has become the ultimate goal of every club calcistico italiano (Italian football club), pursued with fierce competition and followed passionately by millions of fans.

Winning the scudetto is not just about topping the league table—it means enduring a long and grueling season filled with tactical battles, dramatic goals, derby infuocati (heated rivalries), and moments of glory or heartbreak. The teams that contend for the scudetto are often referred to as grandi squadre (big teams), and include legendary clubs like Juventus, AC Milan, Inter, Roma, and Napoli. Each championship is remembered not only for its winners, but also for its heroes—attaccanti prolifici (prolific strikers), portieri imbattibili (unbeatable goalkeepers), and allenatori carismatici (charismatic coaches).

For fans, the scudetto represents more than sporting success. It is tied to local pride and identity—being crowned campioni d’Italia (champions of Italy) gives a city bragging rights and a place in football history. Streets fill with tifosi in festa (celebrating fans), fireworks light up the sky, and songs echo through piazze affollate (crowded squares) when the title is secured. In cities like Napoli, winning the scudetto has sparked celebrations so large they became part of collective memory, as happened in 1987 and 2023.

Beyond football, the word scudetto has entered Italian language and culture as a metaphor for excellence and supremacy. It’s occasionally used in contexts such as basket, rugby, or pallavolo (basketball, rugby, or volleyball), where national league titles also carry the term. But its strongest resonance remains in football, where every season’s saga is ultimately a quest for that small tricolor symbol—a dream chased by teams, players, and supporters across the country.